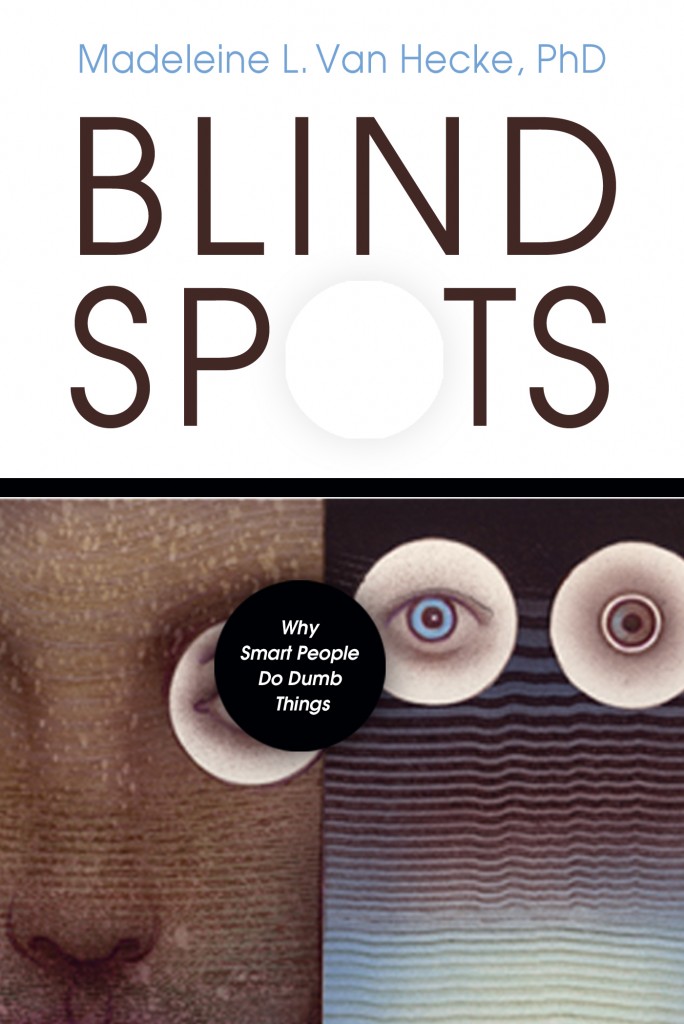

I had an opportunity to catch up with Madeleine Van Hecke, Ph.D. (Elmhurst, IL) author of Blind Spots – Why Smart People do dumb things. I stumbled onto this book while finding books based on my reading habits. It is good to know that Amazon did not have a blind spot for understanding what I like to read and learn about or I would never have discovered Blind Spots – Why Smart People Do Dumb Things! This book not only has great alignment with my book Just Ask Leadership – it brings you face to face with your own blind spots, without judgment and then prescribes some useful techniques that will attune you to increase your awareness and in some situations shine lights on some dark corners of sight, sound and thinking. Madeleine is a licensed clinical psychologist, an adjunct faculty member at North Central College in Naperville, IL, a lecturer at Common Ground (Deerfield, IL) and a speaker, trainer, and workshop leader for Open Arms Seminars.

During her tenure as a full professor at North Central, Madeleine won numerous awards for teaching excellence. Ten years ago, she resigned her full-time position in order to have more time to write, but continued as an adjunct instructor, teaching graduate courses in critical thinking and creative thinking. A creativity exercise in one of these classes led her to develop the family word game, Wicked Words, which was carried nationwide by Barnes and Noble during one holiday season.

As she continued to teach—and learn about—creative and critical thinking, Madeleine became more and more intrigued by the apparent “stupidity” of adults. “For as long as I can remember, I have been fascinated by the quirks of the human mind,” Madeleine comments. “I mean, really—how could the bank robber not only rob his own financial institution but write the hold-up note on the back of his own deposit slip?”

She began to see apparent “stupidities” as a puzzle to be solved. “I was reading all this research that confirmed my personal observations of how incredibly astute and logical children, even preschoolers, can be. At the same time, I was aware of studies that showed adults were often illogical and made some incredibly dumb decisions. Why? What was going on here? Are we to believe that human beings reach the peak of intellectual development at age five, and go downhill after that? Not likely.”

Madeleine eventually developed the metaphor of blind spots to account for “why smart people do dumb things.” In Blind Spots, she shows how our assets as thinkers create the very blind spots that become our worst liabilities.

Most recently, Madeleine has been applying ideas from Blind Spots to solving organizational problems. Madeleine draws on basic ideas in Blind Spots to help people discover perspectives that will help them deal with frustration, understand one another better, see more options, build trust, and lessen cynicism.

Gary Cohen: As you know our readers come mostly from leadership roles. How does your book address issues of leadership?

Two of the biggest challenges that leaders face are how to make wise decisions and how to communicate effectively with others – their customers and clients, their venders, heads of other departments, and their own people. Leaders who are able to overcome their blind spots are better decision-makers and communicators. Let’s look at why that’s so.

First, what keeps leaders from making wise decisions?

Madeleine Van Hecke: Sometimes we make assumptions that turn out to be wrong; sometimes we fail to see the big picture; sometimes we fail to base decisions on solid evidence. All of these errors can be thought of as blind spots. For example, in the 1980’s the film industry tried to use copyright laws to prohibit home ownership of VCR’s. Industry leaders were afraid that fewer people would go to the theaters if they could view movies at home. They had a blind spot. They failed to see something that is obvious in retrospect – they failed to realize that video rentals could become a major source of revenue to the industry.

Second, what keeps leaders from communicating effectively with others?

Madeleine Van Hecke: All too often we fail to take the perspective of the other person into account, a common blind spot. When leaders fail to understand what their potential clients or customers are thinking, sales drop. When they fail to grasp the perspective of the people reporting to them, initiatives can come to a standstill. Blind Spots helps leaders become aware of common blind spots and offers strategies for overcoming them.

As a leader what will be the key takeaways you would have after reading your book?

Each of the ten different chapters in Blind Spots addresses a different blind spot. Then each chapter offers practical suggestions on what to do to avoid blunders caused by that blind spot. Leaders can use the chapters to identify the blind spots that most often personally give them trouble, and then experiment with the strategies to see which help them. Often these strategies are very simple. For example, the common blind spot of failing to see the big picture is essentially a case of failing to see how some larger system is affecting a problem situation. To overcome this blind spot, leaders can train themselves to routinely ask how the larger system is influencing the situation that they are trying to improve. Once at a meeting on how to encourage more honest communication, one member of the company’s leadership team asked: “Is there anything about our organization as a whole that discourages honest communication?” The room got very quiet. That question brought the discussion to a standstill because people recognized its importance – and then it fueled an intense and crucial discussion.

In chapter one you write about that it is blind spots, rather than stupidity, that cause most of the apparent stupid beliefs, decisions and actions we observe. How have you been at convincing leaders of this? And what have you said that successfully convinced them?

At one recent meeting, the organization’s leaders had a number of concerns about younger employees. For example, they said things like, “People write reports and don’t seem to understand that they won’t convince the board of the necessity of the program they are proposing because they’re not offering any substantial evidence to back up what they are saying.” After hearing several different complaints, I asked this upper-level leadership group how they had learned to think more carefully and make better decisions in these areas. It turned out that each person had a story about a Big Mistake they had made when they were younger, a mistake that all too painfully demonstrated to them what goes wrong when we get it wrong. And each also had a supervisor at the time who insisted that they personally right the mistake.

Memories like these remind leaders that smart people – the smart people in that room, people smart enough to now hold very responsible leadership positions – sometimes do dumb things. Ask smart people to recall “dumb” mistakes they’ve made, times when they’ve thought “How could I have done that!” Recognizing times when they themselves have had blind spots is a powerful way of convincing leaders that blind spots are often at the root of what appears to be stupidity.

What also happened that day is that the leaders realized a key reason why their younger employees were not developing. It was clear that all too often supervisors corrected the mistakes that their team members made. Some would rewrite the report for the board, for example, rather than having the employee produce a more adequate report. Another might make a phone call to smooth over the ruffled feathers of a client, instead of having the employee deal with the problem and hear first-hand how much the employee’s actions had upset the client. So during this conversation, the leaders also discovered a current blind spot.

What do you mean in your book when you say that people get trapped by categories?

Our minds naturally think in terms of categories. Even a child thinks in terms of simple categories, like “things we eat” and “things we wear.” Thinking this way helps us organize and understand the world. It’s a great asset. But this useful skill can work against us. Remember Silly Putty? The engineers who developed Silly Putty thought of it as a new compound for the rubber industry and then couldn’t think of any way to use it. It took a toy store owner to see the playful side of this material because he could think outside of the industrial category. The engineers were thinking inside the box – because our minds naturally see the world in terms of categories, little boxes. That’s a great advantage most of the time. It helps us organize what we know. But like other helpful ways that our minds work, it can backfire – it can create the blind spot that made the engineers miss Silly Putty.

How does evolution, psychology, and brain function lend itself to us having these blind spots?

Well, that’s a big question and one that we only have a partial answer to at this point. But one example might illustrate how blind spots might have evolved. Neuroscientists today realize that the brain is terrific at noticing patterns. It’s easy to see that learning to recognize the signs that certain animals are nearby, or where certain plants are likely to be found at a particular time of year, would help people survive. We continue to use pattern recognition all the time. For example, physicians use pattern recognition to diagnose diseases. When a particular set of symptoms are present, along with a particular set of test results, they see if that information fits a pattern — a diagnosis. This works well – as long the patient is suffering from a common disease, an easily recognized pattern. But as Jerome Groopman points out in his book, How Doctors Think, focusing so much on these common patterns can also create a blind spot. It can blind doctors to the possibility the patient is suffering from of an uncommon disease, a rarer pattern, so that they continue to treat the wrong condition instead of searching for a different diagnosis.

In business, leaders also rely on recognizing patterns in order to diagnose and then solve business problems. It’s very efficient for the brain to notice a pattern and conclude, for example, that “sales are down because the economy in general is down.” But that might not be true; it might be if we were to look further, we’d see that in fact our competitor’s sales were up, and we’d need to figure out a different explanation for our decline in sales. So it seems that our brains work for us 80 or 90% of the time – but our very strengths in thinking can work against us because they also create blind spots.

How does knowing you have blind spots enhance your ability to counter act them?

Nobody is going to try to address a limitation that they don’t even know is there. So the first step in counteracting a blind spot is to realize that you have it. For example, one leader might recognize that he often gets lost in details while another realizes that she fails to delegate work when she should. Knowing this, each can practice simple strategies to offset their natural inclinations. One leader in fact arranged for an instant message to pop up on his computer from time to time. The message simply said “Are you getting lost in the details?” He’d step back from what he was doing for a moment and consider that possibility. The other leader used the question “Are you the best person to be doing this?” What happens is that after seeing such questions randomly appear from time to time, those questions begin to automatically pop into your head. You begin to ask yourself those questions, you change your behavior when that’s appropriate, and pretty soon you don’t need the computer reminders.

Sometimes employees appear to be slow to catch on, or downright incompetent. How can a leader tell if someone is suffering from a blind spot, or if the problem really is a lack of ability or lack of motivation to do a good job?

I always start with the possibility that the person’s behavior is due to a blind spot, for two reasons. First, it often is due, at least partly, to a blind spot. Secondly, talking about the problem as a blind spot tends to take the sting out of the conversation. It is less judgmental, and therefore less likely to put the employee on the defensive. So when someone’s behavior is making you angry, I suggest going “from furious to curious.” If you ask the person “Why did you do that?” in a tone of voice that is genuinely curious rather than furious, you are likely to discover something that the person misunderstood that led to their apparently “stupid” behavior.

I think experienced people can easily forget that what is obvious to them is not obvious to someone who lacks their background. One joke that makes the rounds related to tech support describes the technician on the phone asking the person, “Is the cursor still there?” To which she replies, “No, he left the room.” This is funny because it captures the frustration of both the tech person and the person being helped. But my point is that not recognizing the technical language of a field is not a sign of stupidity, but a sign of inexperience. It reflects the fact that “you don’t know what you don’t know” – a blind spot. No one is born knowing that “you have to press ‘enter’.”

Let’s say that you talk with an employee who is falling short on the job and it doesn’t seem that a blind spot is involved. Instead, you find that the employee recognizes what they should have done, but failed to do it. You are then responsible as a leader to figure out how to address the problem. Maybe the person just needs additional training; maybe they are in over their heads on the assignment and you, as leader, need to reassign them so that their abilities match their job challenges more closely. If the problem is simply lack of motivation, then that becomes the issue that you have to address. But so often we jump to the conclusion that indifference or laziness is the cause before we know the whole story, so I try to give the other person the benefit of a doubt and explore what went wrong.

With the pace of the world moving past light speed how does one overcome the blind spot of “Not Stopping to Think, Jumping to Conclusions, Not noticing”?

It’s true that it takes time to be reflective. Leaders have to believe that the long-term benefits of taking more time to think is worth it. However, two things might motivate leaders to make more time to think. First, often a very small investment of “thinking time” pays off large dividends. For instance, in the example above the leader failed to address his team’s reactions to the change initiative that he announced. If he doesn’t realize this, it’s highly likely that the initiative won’t go well, and on the back end he’ll spend lots of time trying to correct the situation. Secondly – and this is the good news that comes out of recent brain research – we can make “stopping to think” a routine that we build into many situations. We can use certain key phrases or situation as a trigger to remind us that we need to think further.

For example, a leader might train themselves to listen for the phrase “That will never work.” Brad Kolar, one of the co-authors of our newest book, The Brain Advantage, suggests that when someone makes this statement leaders should respond by saying, “Oh, tell me all the reasons that this idea will never work.” The reasons that the person then offers really represent his or her assumptions – so that the leader can then raise other questions, like “how sure are we that your assumptions are true?” The point is that when leaders get into the habit of raising questions that cause people to think, the thinking process is streamlined. Leadership team members begin to raise those questions themselves; people begin to automatically step back for a moment and think about what they’re doing.

What do you mean in your book when you refer to “our tendency to habituate?”

We get used to whatever happens on a regular basis. As a simple example, we may really notice the smell of dinner cooking when we first enter the house, but after a few minutes we “habituate” and no longer notice it. Similarly, we might fail to notice the smell of smoke if it builds up very gradually. Leaders get used to whatever commonly happens in their organization. That’s why leaders might not even notice that a creeping cynicism, for example, has invaded their organization. It helps to have someone unfamiliar with your organization give you some feedback about it. They are like the person who enters the building and immediately smells the smoke. The new employee might notice what the experienced leader might miss.

In my book, Just Ask Leadership, I have a chapter that is entitled “What happened when I blinked?” Do you have an opinion on this discussion Gladwell makes in his book Blink?

In Blink, Gladwell argues that decisions made by the seat of our pants are often as good as, or even better than, decisions based on painstaking analysis. Gladwell himself acknowledges that some seat of the pants decisions turn out to be terrible. But his examples emphasize intuitive decisions that turned out to be right because Gladwell wants show that we should respect intuition, not disparage it. So Blink celebrates the value of intuitive thinking and pokes fun a bit at careful, analytic reasoning. But to my mind, Blink oversimplifies the issue. It’s a mistake to enthrone logic as the sole and sure-fire way to Truth, but it’s also a mistake to blithely accept every whim as inspired. The strategies in Blind Spots encourage you to respect your intuitions, but also to take some time to validate that they are correct before you act on them.

Madeleine, Just Ask Leadership came up with an assessment that helps leaders see that they either lead from a place of knowing or not knowing. We found that those that lead from a place of not knowing far exceed those from a place of knowing. Your chapter about wrong, but never in doubt touches on this. Can you explain?

As the chapter title says, some people are “often wrong, but never in doubt.” Most leaders have gotten to their positions because they are successful in many ways. They have expertise and typically make good decisions. This is good. The problem is that leaders can become so sure that they are right that they miss other good ideas, or even miss seeing potentially serious problems with their own ideas. If you lead from a place of “not knowing,” you’ll be more open to possibilities – you’ll also more readily question your assumptions, some of which may turn out to be ill-founded.

How do you counter act the issues of fuzzy evidence especially when you have already made up your mind what is good and bad about the situation?

Once we’ve decided that we know what is true, we tend to only notice data or examples that confirm what we already believe. Psychologists have long recognized that we have this “confirmation bias” – we seek evidence that confirms our beliefs and discount evidence that calls those beliefs into question. It takes intentional effort to offset this bias. Leaders need to train themselves to ask questions that would throw a spotlight on evidence that might contradict what they believe to be true. Simply asking, “are there any counterexamples?” or “where would we need to go in order to discover whether there is data that does not support this idea?” can be very helpful. One leader I know required his team to present the best arguments they could find against the idea they were proposing. Assigning someone to play a devil’s advocate role can also work well.

Is there any topic that I did not ask you about that you would like to comment on?

I’d like to say a few words about my newest book, The Brain Advantage, and how it relates to Blind Spots. Like Blind Spots, The Brain Advantage: Become a More Effective Leader Using the Latest Brain Research (Prometheus Books, 2010) has a strong practical bent. It describes recent brain research and then emphasizes what leaders might do differently if they were to take that research into account. What I realized in writing The Brain Advantage was that brain research sheds light on our blind spots.

For example, brain research shows that the brain creates a sense of certainty, a feeling that we are right. This is the same feeling you get when you say, “I know the answer, it’s on the tip of my tongue…” You can’t come up with it, but you are certain that you know it. In his book, On Being Certain, neurologist Robert Burton shows that the brain creates this sense of certainty – and that sometimes the brain creates this sense of certainty even when we’re wrong. For example, Burton describes a stroke patient who continued to insist that a huge antique table had been stolen from his apartment and replaced by a phony replica, even as the patient acknowledged that this would have been impossible to do. Because of his stroke, his brain made him certain that the table had been replaced, despite all the evidence to the contrary.

The idea that the brain creates a sense of certainty helps explain the blind spot discussed earlier which causes some people to be “often wrong, but never in doubt.” This is also a good example of how talking in terms of blind spots makes it easier to point out areas that need improvement. Which conversation is likely to have a better outcome? One in which we accuse a leader of arrogance, or one in which we raise the possibility that a false sense of certainty is leading that person to be overly confident of their ideas or overly quick to reject the ideas of others? Knowing more about the blind spots we have, and about how the brain works to create them, can give leaders an edge to make better decisions themselves and to respond more effectively to their people.

Gary, if you’re able to mention the two websites for my books, I’d really appreciate it. They are overcome blind spots and the brain advantage.

Related Blog Posts:

5 Best Questions for leaders to Build Resilience Against Blind Spots

5 Things You Can Do To Eliminate Blind Spots

Leadership Tip: Do You Know You Have A Blind Spot

Recognizing Blind Spots – Exclusive Interview with Author Madeleine Van Hecke