“We don’t see the world as it is. We see the world as we are.” –Anais Nin

The health and efficiency of an organization can often be judged by how often triangulation occurs and whether or not it is tolerated by leaders.

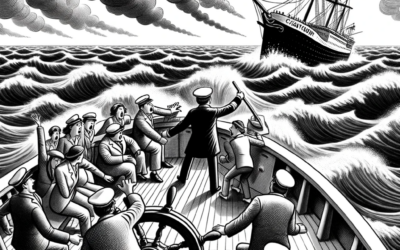

Here’s how triangulation starts: Victims approach Rescuers with information about what a Persecutor has done. From there, the drama can unfold in many ways. Rescuers often hold power in the organization, and, when their compassion and sense of justice are stirred, they may try to wield this power. Maybe the rescuer calls in other alleged victims for verification or strategic discussions. Maybe the rescuer confronts the persecutor or slyly tries to orchestrate a confession. Maybe the rescuer tries to sabotage or exact revenge on the persecutor. Or maybe the rescuer takes pains to make sure the victim is protected in the future and/or compensated. In any event, a lot of organizational time and energy has been spent. And it’s not over.

Persecutors, after all, aren’t always clear-cut villains. They may very well feel that they are the victims, and they may have grounds to prove it. They may be unfairly blamed by others who operate from a victim’s mindset in order to avoid work or blame. Rescuers aren’t always reliable either. Some relish the power that playing the rescuer affords them. They may enjoy hearing and even spreading rumors. Or they may like pretending that they are, in essence, trial judges and above the fray.

Is it any surprise that triangulation can bring organizations and their productivity to a standstill?

The most effective way, I’ve found, to stop triangulation is for the CEO to communicate that employees caught engaging in triangulation will be fired. It is amazing how fast the behavior changes! Of course, there are other less extreme ways to deprogram the triangulators. Whenever a victim approaches you (as a rescuer), simply ask if he or she has already spoken to the persecutor. If not, instruct the victim to do so and report back on the conversation. Reporting back is important because otherwise the conversation between victim and perpetrator likely won’t happen.

If the victim feels uncomfortable having the conversation directly with the persecutor, offer to sit in on the meeting to help support better communication in the future. When you attend this meeting, be sure to act as a facilitator, not a rescuer. If you pass judgment or take sides, the other two parties won’t be as inclined to own and resolve their issues.

It’s tempting to play victim, persecutor, and rescuer at times, but leaders need to encourage and practice direct conversation.